The Problem of Communion: On Church Parties

No, not those kind of parties. Also I have a worthless observation on the Conclave.

Last post in this Problem of Communion series, I examined a model of communion that I call the Communion of the Willing.

The Problem of Communion: Revisiting the Communion of the Willing

Much as I did in my last entry in this series, I’m thinking out loud again and wrestling with the Problem of Communion. So your forbearance with any disorganization or omissions is appreciated.

In this model, communion and fellowship are largely determined on an ad hoc basis: does someone or a church practice orthodoxy and orthopraxy (right practice)? Then there is communion, at least on a de facto basis. That even if denominations/jurisdictions are not in de jure communion.

Often this is practiced within a denomination as well. Issues relating to orthodoxy and orthopraxy can divide and prevent full communion within denominations. One example is that many in the Anglican Church in North America and in the Church of England will not take communion from a woman priest although both churches have women in Holy Orders. In such situations, one option is to stay in a denomination but form church parties with people in agreement. These parties are mostly informal, yet often people in different parties have little to do with each other.

Of course, this is not ideal. St. Paul sharply criticized the church at Corinth for the church parties and divisions among them. (I Corinthians 1:10-13; 3) But parties avoid, at least for a time, the greater division of leaving or splitting a church.

The Church of England is a classic example of a church with parties, especially since the beginning of the Oxford Movement in 1833. They are so because, for most English Anglicans, it is unthinkable to leave the Church of England. The Church of England is too much embedded in English and Anglican identity (although that connection is weakening). This is the main reason UK Anglican denominations outside the Church of England remain very small even though the C of E has become increasingly apostate.

So in the 19th Century, the Tractarians and later the Ritualists stayed in the C of E although some went to Rome. We call these Anglo-Catholics today although the A-Cs have parties among themselves also. (Have I ever mentioned Anglicanism is messy?) The Evangelicals stayed as well, although a few became Dissenters. Nor did these parties attempt to split the Church of England. Nor did other parties such as the High Churchers and Latitudinarians.

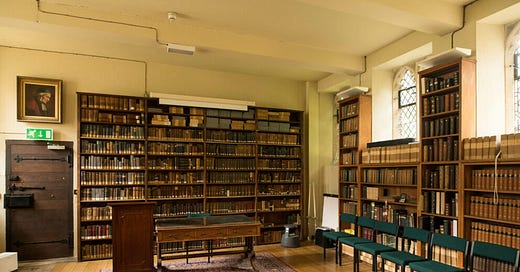

Instead they fought with each other. Man, did they fight. They fought in print. And I am not referring to Tracts of the Times which were scholarly and irenic in tone. I think mainly of various pamphlet wars. If you go to the Ursell Room at Pusey House, along the walls are shelves upon shelves of pamphlets published by warring church parties.

(By the way, the titles to many are amusing and hold nothing back. I hope to study and write more on these.)

Too often the fighting went far beyond words. The Ritualists and their liturgies enraged those who hated “popery.” So much so there were riots in the streets and even in churches. And short of riots, Ritualist services were often disrupted. One may find several examples of all this here, including disruptions at St. George-in-the-East:

In these days of liturgical diversity, with the general public largely indifferent about what goes on in churches, it's strange to think that 150 years ago, because of changes to the style of worship, thousands of people stormed a church Sunday by Sunday for several months, bringing in their dogs, lighting their pipes and attempting to set fire to the furniture, throwing their caps in the air, heckling and jeering and catcalling throughout the sermon and singing rival songs during the hymns. Rule Britannia and God save the Queen were the favourites.… Dean Stanley (of Westminster) attended on one occasion and, having no ear for music, nor eye for what was going on, is said to have pronounced the hymn-singing to be 'most hearty’….There were riots outside the church too, so that the Rector needed a police escort to escape from a side door back into the Rectory.

All this is what happened at St George-in-the-East between May 1859 and July 1860. Questions were asked in both Houses of Parliament, where there was little support for the Rector and his pleas for more effective protection. Indeed, because of the actions of the Vestry it was members of the clergy and their friends, rather than the rioters, who were prosecuted.

Oh yes. They fought in Parliament and in the courts as well. One result was the passage of a bill aimed at Ritualists, the Public Worship Regulation Act of 1874. Under that act, a handful of priests were eventually imprisoned. And there were numerous other actions taken against the Ritualists in the courts.

One may well ask why stay in the same church when matters are that implacable and hostile? Again, leaving the Church of England was unthinkable for most committed churchmen. And (I know my Roman Catholic friends will get a laugh out of this, but still… ) Anglicans are more averse to schism than most Protestants.

The Roman Catholic Church also has parties, in case you haven’t noticed in the lead up to the Conclave. And they also are willing to suppress each other when possible. Pope John Paul II rightly acted against the Liberation Theology party. Pope Francis wrongly attacked Traditionalists and suppressed the Traditional Latin Mass. And don’t get me started on the James Martin crowd or the German bishops.

Yet, with very few exceptions, those Papists stay in communion with Rome because that is hard wired into Roman Catholic ecclesiology. Communion with Canterbury used to be hard wired into Anglican ecclesiology, but much less so now. And even in the past, communion with Canterbury was more a formality than communion with Rome.

The question remains whether church parties are preferable to leaving or splitting when there are such sharp and intractable differences. Addressing that question is as messy as Anglicanism and will have to wait for another day. But I will say that if there are profound differences in a church and if dividing or splitting are not acceptable options, then church parties are a logical if unpleasant adaption to the Problem of Communion.

——

Since the Conclave is the church topic of the moment, I will chime in with a worthless observation and/or prediction:

A quick election would be bad news. It would mean the libs easily got their choice or one of their choices. So I, for one, hope there is no Pope today, the second day, and we at least go into a third day.

If the Conclave goes beyond tomorrow, that probably means the Bergoglians are meeting stiff resistance. So today and tomorrow might be telling.

Yes, I want a good long Conclave. And not because I want the Cardinals to suffer — although I would not object to that.